Inside the Dunes Dwelling: Door County’s Hobbit Home

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

On South Cave Point and Glidden drives, there are dueling stretches, both lake and woodside, of homes and cottages that all have unique stories.

One home in particular sits on a two-acre plot on South Cave Point Drive. This home had acquired several nicknames through the years, such as “The Dome” and “Mushroom House.” It is all too familiar to summer visitors getting lost navigating to Whitefish Dunes State Park.

The vacant dune dwelling has always been a mystery, but the home had a life of its own before it harbored several stories about how it came into existence.

The Dome house’s origin begins with my grandfather, Albert Quinlan. He was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1928. As a young man, he began his career as an art director at Gardner Advertising, but always had an urge to become a solo artist. In 1943 he met Margaret (Mickey) McMullan. They married in 1945 and had 11 children. From what I have been told, it was quite the chaotic household — he was an advertising professional, she a St. Louis Globe volunteer delegate working to improve the quality of life in the St. Louis community, and both were raising a large family.

When I asked my dad, the fourth oldest of the bunch, what is was like growing up in a house with 12 other people, he said, “It was noisy and busy but lots of fun!”

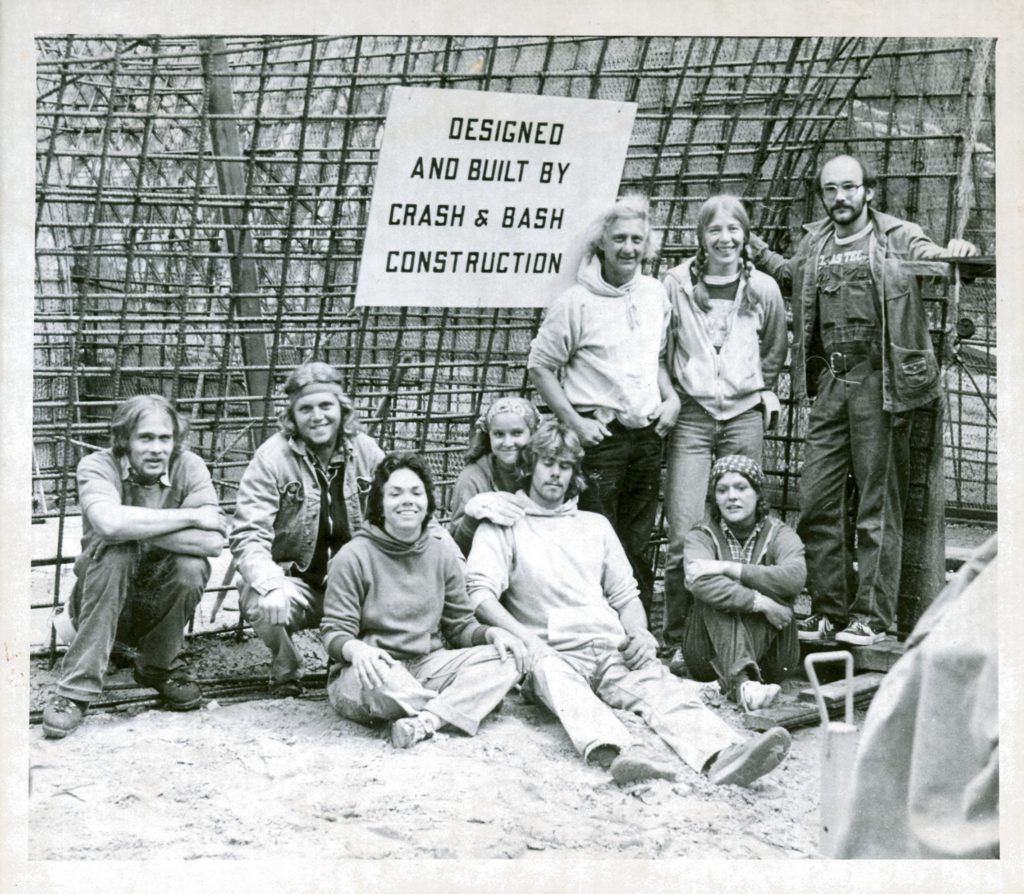

Al Quinlan designed the Dome Home during the energy crisis of the mid-1970s. Built into the side of a sand dune, the concept for this “earth” home was that built into the earth, it would maintain a temperature of 55 degrees, requiring minimum heating and cooling. The home was built in 1978 of chicken wire, rebar and Ferro cement with an open concept design. Photos by Len Villano.

During the summer months in St. Louis, my grandparents knew all too well that the heat had no mercy. At the recommendation of a family friend, all 13 family members packed into a 1953 Ford station wagon and drove 17 hours (due to the lack of an interstate) to the peninsula to escape the relentless heat.

After a couple of summers spent renting a small cottage on the lake, Mickey and Al wanted to make Door County a permanent fixture in their lives. In the late 1950s they purchased 11 acres of lake and woodside land, and in 1960 broke ground on 5060 Cave Point Drive.

As a talented artist, Al was able to take an idea and bring it to life. It was only fitting that he designed the first home he and my grandmother built in Door County. My father vividly remembers this process.

“He designed the house, built all the furniture, and made a model of the house and gave it to the builders and said ‘Here, it’s to scale, just build it.’”

The furniture, triple bunks, light fixtures — he designed it all. With the help of his sons and daughters, “the cottage” (as the name carries on today) and the furniture in it was built in no time. It was, and still is, a place where the Quinlan children, grandchildren, neighbors, and friends come to gather, eat, talk politics and relax.

Al and Mickey were long-term members of the Door County community. Al was very involved in the artistic community, and Mickey was busy rearing their 11 children. In 1970, both Al and my grandmother moved up to the peninsula permanently so he could pursue his independent artistry. My aunts and uncles say he wanted to pursue his dream of being an independent artist and live according to his own terms. During this time, Al photographed landscapes all over Door County and made serigraph prints from the photos. Many of his prints are held in corporate collections throughout the country.

In 1976, Al acquired the land that is now 5015 South Cave Point Drive. My grandfather’s imagination started to formulate plans and ideas for the Dome house, in which he would live independently and appreciate the beauty of Door County once again.

My dad said that initially some of the family members and friends were skeptical but as it came together, excitement grew.

The home has many interesting design features, including a concrete dunescape, indoor botanical area, and open floor plan. What may have inspired such a vision? In 1973, domestic oil production was declining, there was an oil embargo, and the world was in an energy crisis. In March of 1974, the embargo was lifted but the effects of the crisis lingered through the decade. As a result, the price of oil skyrocketed and policymakers in Washington, D.C., were moved to redefine America’s relationship with fossil fuels. The urgency of the matter was felt by citizens everywhere, including my grandfather.

The design of the home stemmed from the idea that an “earth” home could be built to require minimum heating and cooling, and remain an even 55 degrees from the earth. As his children describe the idea, “It was creative and resourceful. He was passionate about, and in tune with, the environment. He was an independent thinker.”

In 1978, Crash and Bash Construction took on the project. Not only was the concept of a self-regulatory home extraordinary but the construction itself was no small feat. First, the sand dune that the home is tucked under had to be moved then pushed back over the roof once complete. The two domes are molded from chicken wire and rebar, and sprayed with Ferro cement. The cement clung to the chicken wire base, measuring four inches thick. This technique provided the strength to support the “replaced” four to six feet of sand. The inside walls are coated one-inch thick with cement and painted white to diffuse sunlight. The divider between the kitchen and living space is a large ship’s boiler. This would heat the home in case the average 55 degrees wasn’t warm enough in the winter. And if that didn’t cut it, there was a backup heating system (you know, just in case).

With the help of architect Don Hansen, Al was able to make his vision a reality, complete with a separate workspace and an indoor botanical area for ecological measure. This botanical area was purely designed for a green, visual element inside the house. It surely provided a more “earth-like” tone.

In addition to being inspired by the energy crisis, my family often cites that Al’s inspiration came from Spanish architect Gaudi, and how his organic shapes inspired his wave-like concrete shapes.

After one year of construction, the unconventional house was ready to be made a home. Al lived and worked in the open concept dunescape until 1982, when it was sold to the Hammel family. The home was only occupied on a part-time basis, with minor renovations taking place, but no permanent residence was ever taken. For years the home was victim to vandalism. Trespassing and graffiti took away from the home’s beautiful mystic, and instead created more of an eerie, time capsule of a home.

Only a few years ago the house was back on the market again. It was only fitting that one of Al’s own children, my aunt Mary Grace Quinlan, bought the home in November 2016. The new ownership puts the home back in the Quinlan name, and also bodes the question as to what is in store for the Dome house. When asked, my aunt simply stated, “I’m not sure what the future holds for the Dome house. I just felt that it was important to have it back in the family. It’s our family’s story to tell. The house needs quite a bit of work, but for now we’re going to make it safe.”

And there you have it. Every home has its story, and this one will surely be a Door County staple for some time to come.

Olivia Quinlan was born and raised in Chicago, spending every summer as a child in Door County. The peninsula was a huge part of her life growing up, and remains so today. She currently resides in St. Louis, Missouri, working full time in sales development.