Owls

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Few birds have received more admiration throughout history than those priceless wonders designed for darkness, the owls. Look around you and chances are good that an owl peers down at you in some form of art, or perhaps as a toy or a piece of jewelry. One of the several highly-admired owls in our home is a handsome Screech Owl wood carving done by my dad’s Uncle Wodsedalaek in 1910. Apparently, my

great uncle had seen some of these tiny owls around his farm because I marvel at the fairly good likeness to the real owl. True to all owls, both eyes face forward, but one slight mistake was made. Uncle carved all of his birds with three toes facing forward and one backward when perched. This is correct for songbirds, but all owls when perched have two toes facing forward and two backward.

Screech Owls may nest in Door County but are not common. Their song is gentle, quivering, whinnying, slowly descending and easy to recognize. One reason that this small 7 to 10-inch owl is not more common is that the two considerably larger nesting species in the county, the Barred and Great Horned Owls, both are known to prey upon the Screech Owl.

Late fall and early winter are courtship times for the owls, and it is then that you stand a good chance of hearing their songs, perhaps more appropriately referred to as vocalizations. Some birders during the annual Christmas Bird Counts use tape players in the early morning before sunrise and evening hours after dark in hopes of having owls answer. Frequently, in past years I’ve heard Great Horned Owls in the distance while I was outdoors waiting for our first pre-dawn breakfast guests to arrive in mid to late-December. It’s one of the easiest owl songs to recognize – “who-WHOOoo-who-who-who,” usually a five-part vocalization sung at around middle C.

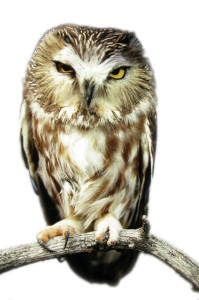

Accurate records of the nesting owls of Door County include the Great Horned, Barred, Long-eared, and Screech. I personally believe that there are also Saw-whet Owls nesting in the county – they are very tiny, 7 to 8 ½ inches, usually live in moist dark swamps, and are extremely secluded in their habits. It is during early spring, March to May, and later in fall that we see and hear them as they migrate through this region from their northern Wisconsin nesting grounds. I also believe that Short-eared Owls nest here. Even though not proven, it’s just a matter of locating a nesting pair. I have photographed them here in winter. The problem is that they move around a lot, to where their main prey, mice and voles, are present.

Owls which have been observed here, but are not known to ever nest in our area, include the Snowy Owl, Great Gray Owl and Hawk Owl. All three typically are day fliers and hunters which places them apart from those which nest here. The Snowy Owl is quite unmistakable but the remaining two offer challenges in correct identification. The 14 to 17-inch Hawk Owl has a long rounded tail and, when you might be so lucky to see one, frequently is perched on an electric power line.

The extremely tame and approachable Great Gray Owl is very large, 24 to 33 inches, has a rounded

head, very striking parabola-shaped facial discs, and bright yellow eyes which easily set it apart from the somewhat similar but much smaller Barred Owl, known for its black eyes. It was in March of 1997 when

Charlotte and I finally got excellent looks at a Great Gray Owl east of our home. The northern Midwest was experiencing a genuine and wonderful “northern owl winter,” and many sightings and photographs of Great Gray, Snowy, Boreal and Hawk Owls resulted. The owls were forced southward due to an extreme shortage of their small mammal prey in the north.

I was able to stalk through a foot or more of snow, approach very closely and photograph a Great Gray hunting for field mice. The bird patiently perched in the top of a thick growth of Pussy Willows, listened intently until just the right moment, and then soared downward to make its unbelievable and unerring catch of the unseen mouse on the ground beneath the snow.

The large facial discs surrounding this and other owls’ eyes act much like the outer ears, gathering sound and directing it to their inner ears. An article in National Geographic, February 2005, said that a Great Gray Owl can hear a mouse moving beneath two feet of snow while the owl is perched 10 feet up in a tree. The instant the owl reaches the surface of snow directly above the little rodent it must smash through with its face into snow packed firmly enough to support a 180-pound man. The thick layer of feathers, acting in a sense like its crash helmet, thus help to protect the owl’s head.

Dead road-kill owls I’ve examined in the past with my students, including the Great Horned, Barred and Saw-whet, all, true to form, had asymmetrical ear openings designed to help them more accurately judge distances. An amazing experiment with a Barn Owl, known to nest in southern Wisconsin, proved that it could unerringly capture its prey in total darkness.

A current myth is that the flight of owls is silent so it won’t scare its prey away. A much more plausible reason for the soft feathers on the leading edges of its wings, making for silent flight, is so that the wing noise doesn’t drown out the faint mouse sounds the owl is trying to hear. Bear in mind that the owl’s wings are very close to its ears, much farther away from the tiny moving rodent below in the snow or in the leaf litter.

No owl in North America has as great a distribution as the Great Horned Owl. Check your field guide’s distribution map to see how widely it nests on the continent. Our great friend to the raptor, Fran

Hamerstrom, informed us years ago that there are few counties in the U.S. in which the Great Horned Owl doesn’t nest. While small mammals (especially the White-footed Mouse and Cottontail) are commonly caught and eaten by them, this large and powerful owl, nicknamed the “tiger of the air,” is known to also kill and eat skunks. Apparently, the owl is not perturbed in the slightest by the black and white perfume dispenser’s defensive spray. Another frequent food item of the Great Horned is the Common Crow. The mobbing and harsh calling of the crows is often their attempt to drive the Great Horned off their nest or out of their nesting territory. Yes, many Great Horned Owls have eaten crow.

Ornithologists, studying the hearing range of the Great Horned Owl, have learned that they are not led to the low muffled but far-reaching drumming of the Ruffed Grouse. Humans can clearly hear the grouse’s drumbeat of 40 vibrations per second but, lucky for the Ruffed Grouse, the large owl’s hearing does not extend below around 70 vibrations per second.

Owls, in general, especially the Great Horned, are the earliest nesters of all birds in the county. The

Great Horned female often incubates her eggs with snow covering her back, with nesting having begun as early as late January. The reason for this is that the young owls require such a long time to mature and be able to hunt their own food. Young often will remain in the nest for 10 weeks.

Owls are extremely important in helping to maintain good balances of animal life in the various ecosystems. Fortunately, all owls are protected by law in Wisconsin. We have only recently begun to understand the important role of owls in nature. Protecting, preserving and encouraging our owl population will not only benefit humanity in numerous ways but will strengthen understanding of our own place in the great web of life as well.