Questions & Authors: Angela Palm Hopkins, 2022 Hal Prize Nonfiction Judge

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Angela Palm Hopkins’ love of writing developed from her love of reading. This year she will serve as the nonfiction judge for the Hal Prize.

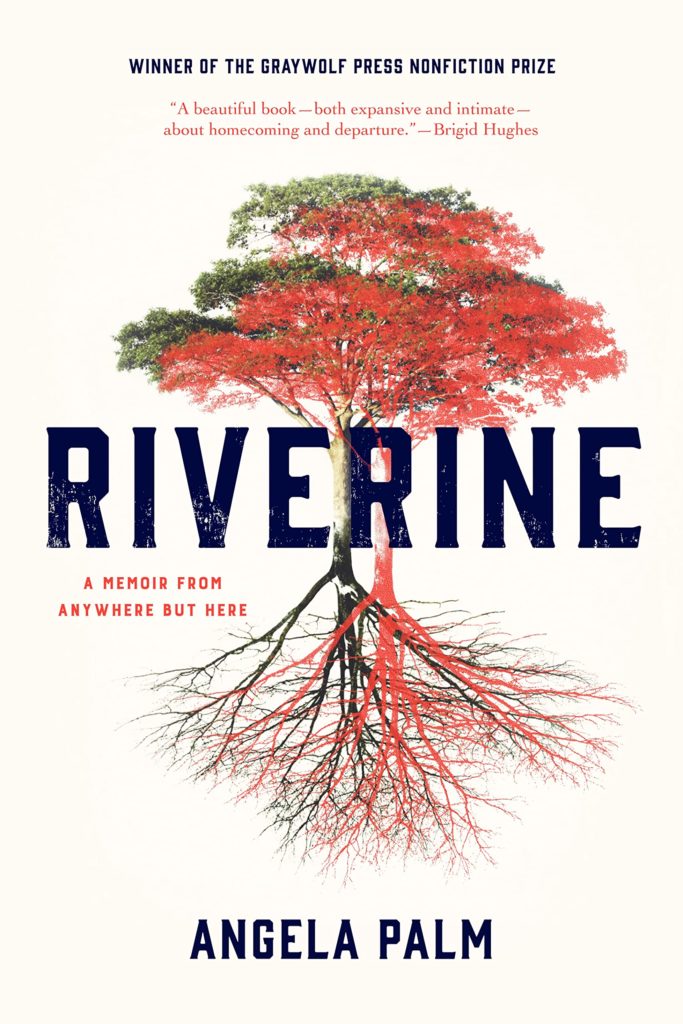

Palm Hopkins was raised in the rural Midwest and earned a B.A. in English and a B.S. in criminal justice. Her book, Riverine: A Memoir from Anywhere but Here, earned the 2014 Graywolf Press Nonfiction Prize, was short-listed for the Vermont Book Award and the Indiana Author Award/Emerging Author Award, was an Indie Next selection and a Kirkus Best Book of 2016, and was named a Powerful Memoir by Powerful Women selected by Oprah.

Palm Hopkins has taught creative-writing workshops and classes at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Champlain College, the New England Young Writers’ Conference, the Kentucky Women Writers’ Conference, the Writers’ Barn and many more.

Her memoir, Riverine, talks about her life in rural Indiana, the boy she loved from afar and escaping small-town life. Though she did escape, Palm is drawn back home as an adult, recalling vibrant and complicated memories of home and family – and visiting the boy she loved, now in prison for a brutal murder.

I recently talked with Palm Hopkins to discuss her writing journey, telling the untold and hard stories, and lots more. Learn more about her at angipalm.com. To submit to the Hal Prize, visit thehalprize.com.

Grace Johnson (GJ): Let’s start off with a big, broad question. What was your writing journey?

Angela Palm Hopkins (APH): So I’ve been a lifelong lover of books and a reader first. As a young person, I started being expressive through writing in ways that very much felt disconnected to book writing. I didn’t really make that connection until later in life but did go to school to study English literature. So I kept that love of books alive but learned how to write and analyze better in connection with writing.

From there I found that writing, editing and a creative connection to how writing can be used through storytelling to make change was something that I could do as a job. I ended up getting called on to do that in every job that I had, whether it was specifically to fill that kind of role or not.

Some old professors started asking me to review their books from an editorial perspective and provide feedback on those. I started taking on freelance work and then, after a little while, realized that I really wanted to write myself and really revisit writing in a serious way.

So I shifted to really focus on that when I was about 30 years old, and that ended in a first novel draft that is still somewhere on the computer and then what would eventually become Riverine.

GJ: Did you have a moment when you felt you could officially call yourself a writer?

APH: Yeah, that’s such an interesting question because writing is the thing that we learn to do after we learn to speak to each other. But writing as a profession, or as something that you identify with, seems to be this other line for some reason, and a lot of people have different opinions on what that line is.

For me, I actually had a lot of impostor feelings around saying I was a writer. What did it mean if I was writing really seriously and loved it and got a lot out of it personally, but it wasn’t getting published? Was that a writer?

I struggled with that for a little bit, but there was a moment that kind of put me on the spot to really claim that [title]. I started getting some publications and really had started spending more of my time trying to be a writer – whatever that means in our world today – and I was going through customs at the U.S.-Canada border.

I got asked, along with other questions, what I did for a living. I didn’t expect to be asked that. And I just decided to really write for a living. So I had to say that out loud for the first time, and that was a really interesting moment for me. So that was a real moment of “this is an identity that I can own.” I can be part of the group of people who call themselves writers, and that gave me a lot of confidence.

GJ: Your book, Riverine, has gotten a number of recognitions and nominations, and it was selected by Oprah as a Powerful Memoir by Powerful Women. What did that feel like for you?

APH: Those have been really incredible acknowledgments and encouragements that the stories that we have – as young people, as people coming of age, as people who feel somehow “other” within the communities that they inhabit – have really valid stories to tell, and it’s worth exploring those in a serious way.

I also think for a long time I thought that I had a regular life that was very uninteresting. But as it turned out, I don’t think anybody’s life is uninteresting. There’s a lot of extraordinary learning to be done within exploring the ordinary and then, as you go through that, you might learn that things weren’t so ordinary, and what can you learn from that, and what does that add to your experience?

Those [recognitions] have given me the confidence to go forward and to widen conversations about rural experiences and socioeconomic experiences that I wouldn’t have had otherwise. It validated the kind of critique or curiosity that I had about the place where I grew up. I’m interested in the stories that no one told you.

GJ: That’s interesting, that kind of exploration of the unknown or untold stories in these small communities, and I think a lot of people in Door County would find that familiar.

APH: Yeah, it’s so interesting. Sometimes it makes some people uncomfortable, but I try to give that discomfort back to people and ask why that is. Why are they so committed to one narrative about the place where they live, and why is telling some other experiences a threat to that? Why can’t there be multiple experiences and multiple truths?

Having gone through that gave me a lot of bravery, and I think it enabled other people to be more brave in their experiences, too, just in some of the conversations that I’ve had with others.

GJ: How did you approach writing Riverine?

APH: It was definitely a process, and it started with fear, as do a lot of things, and it started with trying not to tell that story – trying to tell a different story around it, trying to even write it as fiction. All that did was cause more curiosity around why I didn’t want to tell that story.

Once I got past that point, I was able to explore it more honestly and realize that there were some frictions and some unsettled feelings about certain experiences that I wanted to explore further. So the next layer of that was to really dive into the discomfort and figure out how all these things relate.

I’ve always had a very strong interest in place and mapping and the different histories that are embedded in the single moment, in the single square inch that we are inhabiting at any given time, and how those histories are influencing the present moment. And I wanted to do that.

I tried to, by the end of it, write something that I could defend and that people could read that would be challenging, but that wouldn’t cause them to feel exposed, unhappy or not fairly held up to the light. It’s a learning process, for sure.

GJ: How long did it take you to write Riverine?

APH: I wrote it in probably 18 months or so. The last couple of chapters I wrote as they were happening, so as I was living them – which I don’t highly recommend. I was telling my editor stories about some things that were happening around [the events of the book] and they were like, well, this should definitely go in the book. So that was interesting.

I feel like some of the strongest writing came in the end, where I really got some clarity around what I was really writing about.

One thing that is really incredible about the editorial process is it really takes writing out of the silo that we’re used to and makes it a collaborative process in this way where it pushes you to make the book the thing I always wanted it to be but didn’t know it could be.

That last leg of the process is where I feel like it all comes together, and these last couple of chapters did that and kind of made the whole thing click, and I really felt like I was homing in on what I was always trying to say from the beginning.

GJ: How does your life outside of writing influence your writing?

APH: It influences it a lot. I really believe that you have to go back and forth between living and experiencing and writing – it’s this constant sort of flow of experience back and forth.

Right now I’m writing again, but there were several years prior when I wasn’t because I was working, going through family changes, and it’s almost like growing a new shell. That’s the relationship between me and the work that I’m doing, the life that I’m living, and then writing and reflecting on those experiences.

Having worked with a refugee education program, and working now with a digital-services company that creates technology products that impact people across immigration reform, veteran services and across access to equity and justice, is giving me this way to see some modern experiences and use my storytelling ability to bring attention to how those things are changing through technology.

I love moving across different industries to apply the same kinds of skills and the same kinds of mindsets to how writing can change everyday life.

GJ: Are you working on anything right now?

APH: Yeah, I have a new book that’s about halfway done. It has not been acquired yet, but I’m close to sending it out. It’s a collection that focuses on applying a lens of family experience and domestic life with architecture in domestic spaces in the U.S.

It’s taken me a long time to figure out what it actually is, but I’m really interested in the ways that we as women, especially, relate to our homes, how across the history of modern architecture, we [women] have been withheld from being in control of those homes in so many different ways, and then the ways that we move out of the domestic space to create new ones and new forms that better serve our actual needs.

GJ: Do you have a specific setup or writing routine that you stick to?

APH: I don’t have a writing routine, although I do have a setup. I have this office which is lovely and set up to write, but I never write in it. What I do is take over the kitchen table and don’t let anyone eat in the dining room for a week at a time and spread papers all over the place.

I love being able to see everything – I’m very visual in terms of process. So I print things out a lot; I cut them up; I move them around; I write things on the wall; I do a lot of hands-on crafting. I think it is because I love how so many different things can connect to each other to form new meaning and new understanding, and that’s a very physical process, I think.

One thing I will do sometimes is write on an old typewriter. It forces me to slow down and be really intentional about how I’m putting together a sentence, and I find that it calms my mind. I’ll do this for first lines or first sentences and workshop them on a typewriter to get it right. Same with titles.

GJ: What advice would you give to people who are thinking about submitting work to the Hal Prize?

APH: I really believe in going with your gut on what you think works and what weird thing are you doing that maybe, you know, isn’t exactly a formulaic approach to an essay but that you feel really represents the point you’re trying to convey. I love the relationship between form and function. I’d really encourage people to think about that and how that’s working for them.

You cannot win a prize that you did not submit for. So to all those procrastinators out there, get yourself over that finish line because it’ll feel good.

This interview has been shortened and edited for clarity.