The Cemeteries of Peninsula State Park

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

As a small child visiting Peninsula State Park one brisk autumn, my father took me by the hand and led me across the street from Weborg Point into the woods. We moved precariously down an unmarked, overgrown trail and emerged into a small cluster of gravestones, slightly pitching and yawing from the earth the way headstones seem to after weathering more than a century of seasons. In the silence, my father whispered that these were some of the most significant settlers in Door County and that we should always be sure to visit them, lest they be forgotten.

For some, cemeteries are a place not to dwell – a place of spooky ghost stories from hundreds of years of legends and children’s night terrors. For others, it’s an imperative place of remembering, of communing, and of commemorating those loved ones who’ve slipped across to the other side.

According to the book, Pioneer Cemeteries, by John M. Kahlert and Albert Quinlan, “A cemetery becomes a way a community remembers…it helps us remember the people who first settled in a given spot, and were responsible for the origin of the settlement. It recalls those who provided leadership to make it prosper. It recalls some of the rascals, too, and perhaps the poor and downtrodden.”

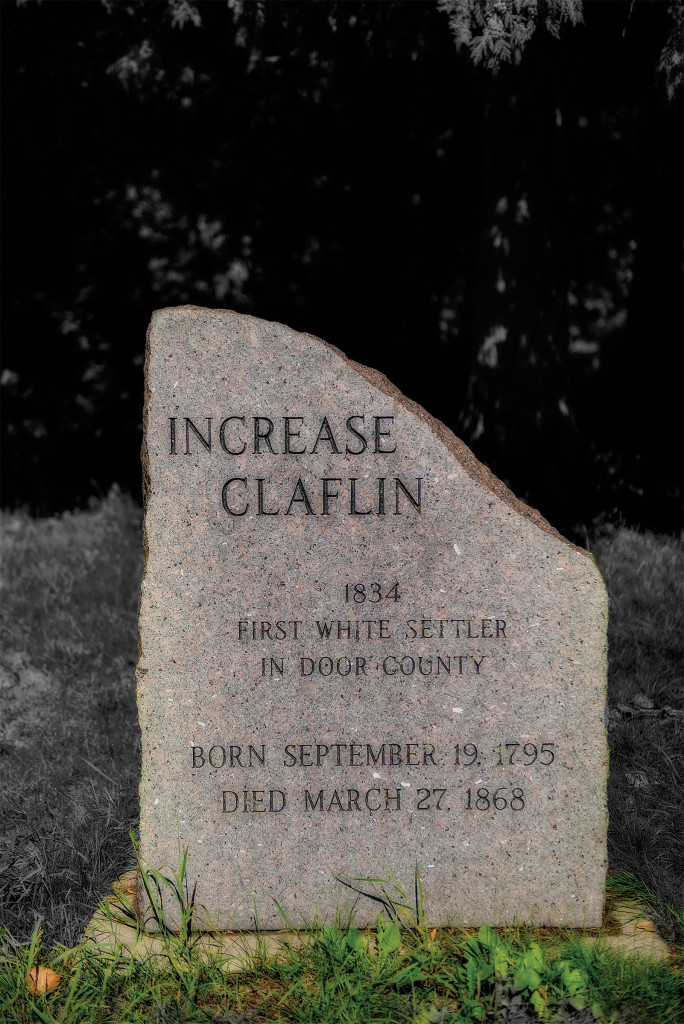

A monument marks the life of Increase Claflin, Door County’s first white settler. Photo by Len Villano.

Here in Door County, specifically in Peninsula State Park, the past, and those who dwell there, is all around us. Two established cemeteries, the Claflin-Thorp Cemetery (also called the Pioneer Cemetery) and Blossomburg Cemetery, hold some of our county’s most treasured forefathers and mothers and our more recent beloved characters. They are a way for our community to recall those early pioneers and more recent deceased who’ve made a mark on this special place.

The Claflin-Thorp Cemetery

The Claflin-Thorp Cemetery is only about 22 feet square, surrounded by a low concrete border, containing the burial plot of more than a dozen evident grave markers. In this plot reside two of the area’s most noteworthy founders and settlers. Increase Claflin, Door County’s first white settler, and his wife Mary Ann built their cabin on what would come to be called Weborg Point on Shore Road in the park in 1844 when he moved north from his first settlement at Little Sturgeon. When Increase died in 1858 at the age of 83, he was supposedly buried across the road in the cemetery. However, his actual grave’s precise location remains a mystery. A monument in the cemetery is erected in his honor.

Asa Thorp, credited as Fish Creek’s first settler in the 1850s, and his wife Eliza Atkinson Thorp, are also buried in the cemetery. The Thorps and the Claflins intermarried, and their descendants still reside in the area. The first Thorp to be buried in the cemetery was Horace, who drowned on May 6, 1856, at the age of 23. Asa himself died in 1907 at the age of 74, having long prepared for his final rest. Unsure of when his demise would come, he had his gravesite dug in advance, worrisome of the difficulties of digging a winter grave in Door County’s infamous bedrock.

“It was said to have been lined with slate which is not native to this area, and to have been covered with a large stone so it would be ready as needed,” writes Kahlert.

The oldest marked grave in the cemetery – and one of the oldest in Door County – however, belongs to Sarah Ann Claflin, daughter of Increase and Mary Ann, who passed away in 1850 at the age of 28. Of course, the word “marked” is used, since people may have been buried there earlier in unmarked graves or with wooden grave markers that would have deteriorated long ago. Additionally, gravestones were often not placed until years after a death and indicated by multiple names on one stone. Sarah Ann’s actual gravestone reads “children of Increase and Mary Ann” drawing the conclusion that it marks more than one burial. Another possible burial in that grave could have been Maria Claflin in 1896, the wife of Asa’s brother Jacob Thorp.

According to Pioneer Cemeteries, “…both were probably buried in a cemetery on the hill opposite the current Omnibus resort [now Little Sweden] which is believed to have belonged to the Chambers family. The Thorps were connected with the Chambers family through Jacob and Maria’s son Roy who married Mathilda Chambers in 1877. Duncan Thorp, great grandson of Jacob and Maria, remembers as a small boy his grandfather, father and a hired man exhuming Maria’s coffin from the ‘Chambers’ cemetery and moving it with team and wagon to the cemetery in Peninsula State Park.’”

Sarah Ann’s remains, along with Maria’s, could have been moved simultaneously.

Other notable burials in the Pioneer Cemetery include two of the sons of Increase and Mary Ann Claflin who served in the Civil War. Claflin, a veteran himself of the War of 1812, sent his only three sons to enlist for the Union, famously saying, “If I had 20 more, they should all go!” Of the three, Albert Claflin came home on sick furlough in April of 1864 and died three months later. His brother Charles had been discharged in 1863 because of consumption. He passed in 1865. The two brothers share a unique double headstone. The third Claflin survived the war and returned to Little Sturgeon, where he was born, to have a family.

Another unique burial in this cemetery is that of Freeman Edwin Thorp, son of Jacob and Maria Thorp. He perished in the infamous tragic wreck of the steamboat Erie L. Hackley in October 1903.

The Erie Hackley made regular trips between Menominee, Michigan and Fish Creek, but on that fateful night encountered a squall, and when the ship went down, 12 lives were lost including Freeman Thorp. The nine survivors were rescued the following morning by a passing ship. Stories like these are just a few examples of the history that surrounds us in our towns and parks.

Blossomburg Cemetery

While Blossomburg Cemetery does not possess as many mid-1800s grave markers as the Pioneer Cemetery, its history and its more recent activity make it one of the most relevant eternal resting places in Door County. One meandering walk through the four acres of graves is like taking a walk through Door County’s more ancient and most recent past. Familiar county names like Thorp are there, along with other familiars like Norz and Bridenhagen.

The cemetery itself has never been sponsored by a religious organization and is currently the cemetery for Gibraltar Township. The name Blossomburg comes from a Scandinavian settler named Ole Klugeland who settled on a farm near Eagle Bluff. The strong winds that come racing across Green Bay from the northwest caused him to name it “Blaasenberg” or “Windy Mountain.” Originally, though, the cemetery seems to have been a private cemetery owned b y the Anderson family before two acres of the land was sold to Gibraltar Township for $100 in 1890. Sixty years later, in 1951, the township bought another 1.9 acres from the state to expand the cemetery (the state had established the area as a state park in 1909). There are 14 marked graves that predate the initial 1890 sale. The earliest gravestone is that of Libbie G. Churches in 1881, who was the wife of Samuel Churches, an early representative of Gibraltar Township on the Door County Board. He is buried beside her.

y the Anderson family before two acres of the land was sold to Gibraltar Township for $100 in 1890. Sixty years later, in 1951, the township bought another 1.9 acres from the state to expand the cemetery (the state had established the area as a state park in 1909). There are 14 marked graves that predate the initial 1890 sale. The earliest gravestone is that of Libbie G. Churches in 1881, who was the wife of Samuel Churches, an early representative of Gibraltar Township on the Door County Board. He is buried beside her.

Patti Podgers, historian and curator/manager of Eagle Bluff Lighthouse in Peninsula State Park, was tasked with helping to sort out some of the older grave markers and plots. When she first moved to Door County 15 years ago, one of her first jobs was working for the Gibraltar Historical Society as curator of the Noble House. One of her first tasks was to carefully help locate which plots in Blossomburg were open. Understandably, after more than 100 years of use, paperwork and family legacies had made it difficult to track, and plots at Blossomburg were growing in demand. Her task was to locate any available plots that had previously been purchased but had no markers. In reality, this task was a difficult one. If a person purchased eight plots, for example, but there are only two gravestones and no descendants to verify burials, a plot possesses a bit of mystery.

“In reality, there could be plots today that have two people marked, but could actually have eight people in them maybe. We have no way of knowing. And we can’t do a thing without paperwork. So we hit dead ends,” says Podgers.

Originally, anyone could pu rchase a plot in Blossomburg, but as demand grew, and space grew short, the Town of Gibraltar decided to only open gravesites to Gibraltar property owners. For a few years, there was a waiting list, until the state of Wisconsin made a property trade with the Town of Gibraltar and the cemetery acquired an additional undeveloped seven acres. The waiting list disappeared, and plots are currently available to township property owners (which includes Juddville, Fish Creek, Peninsula State Park, and Chambers Island).

rchase a plot in Blossomburg, but as demand grew, and space grew short, the Town of Gibraltar decided to only open gravesites to Gibraltar property owners. For a few years, there was a waiting list, until the state of Wisconsin made a property trade with the Town of Gibraltar and the cemetery acquired an additional undeveloped seven acres. The waiting list disappeared, and plots are currently available to township property owners (which includes Juddville, Fish Creek, Peninsula State Park, and Chambers Island).

One family who’s been interred in Blossomburg for decades is the Duclon family. William Henry Duclon became the Eagle Bluff Lighthouse Keeper in 1883 and would spend the next 35 years there, raising his seven sons with his wife Julia. William, Julia, and five of their seven sons are buried in Blossomburg. The cemetery is also home to the resting place of Door County’s famed historian and former President of the Door County Historical Society, Hjalmar Holand, author of Old Peninsula Days, who passed in 1963. While the names of all these well-known, often male, settlers are noteworthy, what’s equally relevant, are the graves of those forgotten or those unmarked. The ones who aren’t celebrated, but are likewise a fabric of our past.

The mystique, quiet solitude, and beauty of both cemeteries are wholly apparent. The two cemeteries carry so much history, so many decades of human life etched out of the wilderness, survived, lost, and endured. As Kahlert writes, “In calling attention to them we pay tribute to the pioneers in Door County who lived, more often than not, in privation and isolation.”

Podgers, along with her husband Jim Johnson, recently purchased their own plots at Blossomburg.

“On my husband’s 65th birthday, I took a break from work, and we picked out two gravesites under a beautiful tree. We have visited Door County since the mid-70s, and for us, this is where we came with our children. If I’m going to be buried any place, it’s going to be Door County, the place that we loved so much…to realize a dream of living here, it made sense that this is where we’d be.”

Photography by Len Villano.