Worker Shortage Endures for Manufacturing Sector

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

N.E.W. Industries is one of those manufacturers that consistently churns out products on the almost invisible outskirts of Sturgeon Bay’s industrial park.

The company has grown twelvefold since Chris Moore – its president, CEO and owner – bought it 21 years ago, eventually relocating it from a 35,000-square-foot Yew Street space into the industrial park. He now owns 150,000 square feet of space.

N.E.W. – an acronym for “Northeast Wisconsin” – peaks at 200 employees. As one of the 62 manufacturers in Door County that collectively employ some 2,300 people, it’s also a key player in making manufacturing the single largest contributor to Door County’s gross regional product, or the value of all the county’s goods and services.

And N.E.W. could be bigger, producing twice its current volume, if only it could hire the employees it needs – particularly machinists – to staff its three full-time shifts.

“There have been situations where we’ll be presented an opportunity for a sizable piece of business, and I have to not pursue it because we just don’t have the capacity from a human standpoint,” Moore said.

Last month, N.E.W. was hiring for almost 50 people. The company has never had a need for so many employees at one time. Karen Urban-Dickson, N.E.W.’s human resources director, said it’s the “absolute worst I’ve ever seen” in the more than 20 years she’s been with the company.

“The biggest single challenge we face, and it’s not inconsistent with the rest of the country, is getting enough people to learn our business and run machines and get involved in production,” Moore said. “I would say it’s the most challenging it’s ever been, with the least light at the end of the tunnel.”

N.E.W. is a CNC (computer numerical control) machine manufacturer. Its 70 major CNC machines, controlled by their human operators, produce precision metal and some composite plastic components. The parts are shipped to customers all over the country in a variety of industries such as defense, construction, motors, trains and home appliances.

“Literally every day you see or use something with our parts inside it,” Moore said. “It’s an old industry and an absolutely huge industry and so much more sophisticated with numerical control.”

A diversified customer base stabilizes N.E.W. even during economic downturns. Total volume decreased during the pandemic in 2020, for example, but the company still had a very profitable year. Business across sectors is now accelerating again, emphasizing a demand for skilled machinists – or those who want to learn the trade – that predated the pandemic.

Employment of machinists and tool-and-die makers was projected to grow 3% from 2019 to 2029 – about as fast as the average for all occupations combined, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Although the machinist jobs are there, societal and demographic factors are channeling employees elsewhere.

The COVID-19 relief plans passed last year and again last month expanded federal unemployment benefits, now through Sept. 4, by $300 a week. This is on top of payments from the state. Moore said applicants have turned down full-time employment at his company because unemployment pays more right now.

“The government continues to pay more people more to not work,” Moore said. “I guess there are some areas of the country where unemployment is higher and there are different issues, but broadly, it’s an area of frustration for all of us. I know that sounds political, but when you have to deal with it, it’s a real thing.”

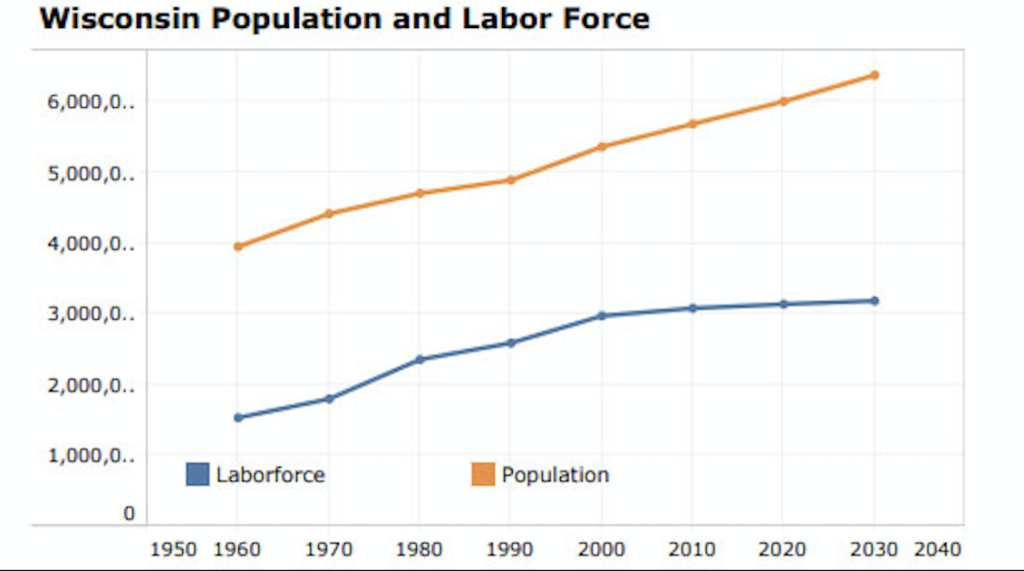

The federal unemployment benefit is temporary. A more entrenched factor depleting the workforce is the country’s aging workforce. The labor-pool curve began to flatten in 2008 in Wisconsin and other Upper Midwest states when the first baby boomers (those born in 1946) reached age 62 and began to leave the workforce, according to a November 2019 report issued by the Wisconsin Department of Workforce Development.

N.E.W. is witnessing that trend firsthand.

“The baby boomers are finally retiring,” Urban-Dickson said. “We’ve been talking for years about how that was going to come. That is here.”

Door County is the fourth-oldest county in the state in terms of median age (52.3 years). More than 38% of the population will be at least 65 years old by 2030. And although Wisconsin’s population is expected to grow, Door County’s growth projections are flat, according to U.S. Census Bureau projections. In 2019, Door County’s population decreased by 3.3%, according to the Wisconsin Demographic Services Center.

“All over the State of Wisconsin and nationally, they’re facing this same worker shortage,” said Steve Jenkins, executive director of the Door County Economic Development Corporation (DCEDC). “Retiring workers aren’t being backfilled. Younger workers aren’t viewing manufacturing as a career path.”

That’s partly because high school students have been encouraged for decades to seek a four-year college degree.

“Many [manufacturing jobs] don’t require a four-year degree, and [the employee can] earn many times more,” Jenkins said.

The median pay for skilled machinists in 2019, according to the BLS, was $21.99 per hour, or $45,750 per year. Only a high school diploma is needed because many are trained on the job. Others learn through apprenticeship programs, vocational schools, or community and technical colleges, often with reimbursed tuition benefits.

“They’re good-paying jobs, and they’re clean jobs,” Moore said. “Young people are so drawn to computer technology, but the machines themselves are so technical and computerized.”

A lack of affordable housing stock and child care options are other factors biting into recruitment efforts.

“The baby boomers, the housing, the child care – it doesn’t matter where you are,” Urban-Dickson said. “Our customers are experiencing that; our vendors are having difficulties. And there’s even more competition in larger population areas.”

Another particular challenge for Door County is its geography. It’s surrounded by water, so workers who don’t live on the peninsula can commute only from the south.

“That’s a unique challenge for us that we have to begin figuring out as a community,” Jenkins said.

One of the remedies for labor scarcity and increased productivity across the state and country is increased automation.

“We’re upgrading the CNC machine itself, but at the same time adding pure robotics,” Moore said. “We’re doing that as fast as we have the tech resources to do it. But we still need more people. Automation is not the total answer. There’s no substitute for having more people.”

Solutions for finding and attracting more people are being developed, Jenkins said. Retaining students who aren’t on a college path by educating them about the various manufacturing paths is one of those.

“We’re involved with the schools,” said Kelsey Fox, DCEDC workforce development specialist. “The [DCEDC] apprenticeship program is going into [its] third year. That’s how we link kids with companies.”

Partnerships between local school districts and local manufacturers is another of those remedies. Some of those are in the planning stages, and individual employers are creating those bonds. Urban-Dickson said they do outreach to schools, participate in the DCEDC’s youth apprenticeship program and provide tuition reimbursement for vocational and technical training.

But just as the problem of achieving a sustainable workforce strategy is bigger than any one company, so the solutions must be as well.

“We’ve reached a point where it’s everyone’s problem,” Jenkins said. “We must look at holistic solutions and not expect somebody else to solve our problem. As a community, we have to solve our problems.”