Struggle for a Stage: Remembering the Fight to Build the Door Community Auditorium

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Johnny Cash.

Victor Borge.

Harry Belafonte.

Ray Charles.

Willie Nelson.

Chubby Checker.

They are among the biggest names in entertainment of the last half century. Thanks to the vision and belief of a persistent few more than 20 years ago, they’ve also performed for audiences in Fish Creek at the Door Community Auditorium (DCA).

Today, the DCA is an integral part of the Northern Door arts community, the premier venue for music and entertainment on the peninsula. It hosts school plays, Grammy-winning artists, middle school band concerts, and even movie screenings. Its presence and connection is so strong that it’s often forgotten that the struggle to get it built in the late 1980s was one of the most divisive and controversial efforts of its time.

In 1983, Gibraltar School’s tiny Old Gym, constructed in the 1950s, was still host of school plays, graduations, concerts, and even the Peninsula Music Festival. Concerts and performances split stage and practice time with physical education classes, assemblies, and practices. Rows of metal folding chairs were lined up tightly to squeeze in audiences.

Then Friends of Gibraltar, a community organization that offers programming and services to enrich Gibraltar Schools, began an artist-in-residency program, and a few folks began talking about building a performing arts venue for the school and community. Anne (Emerson) Haberland, owner of the Edgewood Orchard Galleries and one of the idea’s initiators, said it was clear that if the community hoped to attract great artists to the area to inspire Gibraltar’s youth, it would need a better venue.

She joined a committee within the Peninsula Arts Association to investigate the possibility of building a professional performance facility. The committee became the Peninsula Auditorium Association (PAA), and a dream became a real possibility thanks to a pair of generous sisters who visited Haberland’s gallery.

The Door Community Auditorium under construction in the late 1980s. The building changed the face of Gibraltar School.

The late Laurie Nowack (Hislop) loved going with her husband to the Peninsula Music Festival, which was then held in Gibraltar’s Old Gym, where attendees sat in metal folding chairs. One day she talked to her sister Marian Hislop about how great it would be if there was a quality performing arts venue to host the festival, and when the sisters learned of the PAA committee, they decided to pay a visit to her gallery in July of 1986.

After some small talk, Laurie told her sister to tell Hablerand how they were prepared to help build an auditorium. Haberland wasn’t prepared for what they said next.

“We’d each like to give $500,000 to the auditorium,” Hislop told her.

Haberland’s knees quivered as she tried to grasp what she heard. Later, she called Hislop to clarify. “Did you say $50,000 or $500,000?” she asked in embarrassment. Hislop spoke slowly into the phone. “We would each like to give you $500,000. That’s $1 million, dear.”

With that, Haberland and the Auditorium Association got down to business.

Anne Haberland Emerson colors in the final attendee to show that fundraising for the Auditorium was complete.

A proposal to build the auditorium with $1 million from the sisters and $1.16 million from taxpayers went to referendum in 1988. The lead-up to the vote split the community, and meetings were heated. Supporters faced vehement opposition that Haberland still struggles to understand. “I tried to focus on the positive. If you got mired down in the negative, you’d never do anything but crawl into a hole and hide.” On Feb. 16, 1988, the referendum failed.

Peter Trenchard, owner of Bay Ridge Golf Course and a member of the pro-auditorium faction, was floored. In a roundtable discussion with fellow supporters Haberland, Marian Hislop and George Larsen in 2009, he spoke of his reaction to the vote. “When it failed, I talked to Lon Kopitzke at the Door Reminder and asked if I could buy the front page and just write the word ‘STUPID,’” Trenchard said.

It was an era when the arts were still struggling for respect in the community. The county was undergoing a transformation to a tourism-dependent economy, and many hadn’t yet realized the role the arts could or would play in the new era. If the auditorium was to become reality, Haberland and the committee were going to have to re-group and fight with even greater passion.

Discussions continued after the referendum failure, but when a contingent pushed for a Sister Bay location for an $18 million facility, Haberland and 21 others resigned. Her driving force had been the vision of a facility that would benefit children and the school. A separate facility wasn’t worth the fight. The dream languished until a year later, when Trenchard rekindled the flame with a fortuitous phone call to Haberland from a phone booth outside O’Hare airport.

He had recently seen the impact that an artist-in-residency program with Caryl Yasko had made on Gibraltar students. He couldn’t stomach not trying again. “If I head up a group to raise the money, will you come back?” he asked Haberland. He wanted to raise all the money through donations, then donate it to Gibraltar to build the auditorium. Haberland jumped back on board and the wheels began to turn again, aided by the Hislop sisters reaffirming their $1 million commitment.

Bob Dahlstrom became Gibraltar’s elementary principle in 1987, shortly after the referendum had failed. His support was crucial, Haberland said, even more so when he moved up to superintendent in 1990. “We needed a place for assembly,” Dahlstrom said. “The intent was to build it and not cost the school anything but also have it available for the community.”

Dahlstrom was behind it, but the school board was split. Some didn’t see a need for it, others worried that it would end up costing the school money in spite of the fundraising. “It was not an easy time to be on the school board,” Haberland said.

Some members lost their seats, but the anti-auditorium faction also turned on the Hislop sisters, who had insisted that their donation remain anonymous. One would think that a $1 million commitment would make for smooth sailing, but it became a focal point in the fight. “It was extremely controversial,” Dahlstrom recalled from his current home in Rockville, Maryland. “We would have meetings in the gym and hundreds of people would attend. People thought the money wasn’t really there and that raised suspicions. There was a big push to find out who the donors were.”

“You’re lying,” Trenchard remembered the opposition saying. “You haven’t got a million bucks. If you do, why don’t they come forward?”

The Hislop sisters wanted desperately to remain anonymous, but saw the writing on the wall. Nowack called Haberland and offered to go public if she thought it would help. Reluctantly, the Hislop sisters came forward, a decision that strained some of their personal relationships but quieted a few critics.

Ironically, the fundraising effort fed off the negativity. Each time someone wrote a letter to the editor against the project, Trenchard said, more donations poured in.

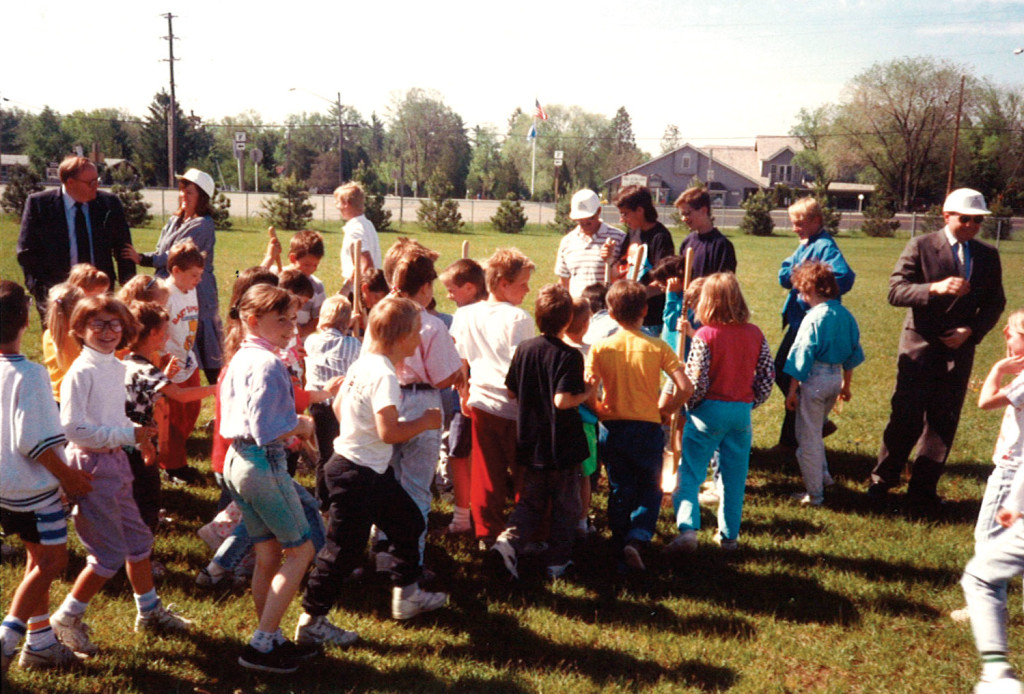

Money was raised in chunks big and small to reach the $2.7 million goal. In May of 1990, ground was broken for the Door Community Auditorium. Gibraltar elementary students lifted some of the first divots.

George Larsen, a retired music teacher and a member of the auditorium committee, dedicated himself to the project’s construction. He became so omnipresent at the work site that the workmen gave him a hard hat and a broom, and to this day a photo of Larsen in his hard hat hangs prominently in the auditorium lobby.

Marian Hislop with George Larsen. Hislop provided pivotal funding for the auditorium, while Larsen was an omnipresent force in advocating for it and monitoring construction.

“George made friends with all of the workmen and I think that added a lot to what we got,” Haberland said.

Also in the lobby, one will find an unusually formatted list of auditorium donors. There is no tier, with large donors separated from small. Haberland saw to this, so appreciative was she of all of the small donations and letters that poured in. She delicately broached the idea with Marian of recognizing donors not by the amount given, but by simply listing them alphabetically. Hislop would have it no other way, she said.

As the auditorium nears its 20th season it faces daunting new challenges. When it was built, the auditorium was essentially the only game in town. “There wasn’t anything else like it,” Dahlstrom remembered. “Some people with foresight had the vision, that there was something it could provide for the community and the school.”

The shine, the uniqueness, and excitement that the community felt at the opening of the facility has faded. In the late 1990s, several venues opened that spread both audiences and donor dollars thin.

The Third Avenue Playhouse, the Southern Door High School Auditorium, and the Trueblood Performing Arts Center all opened their doors. American Folklore Theatre surged in popularity and added fall shows, and Peninsula Players and Birch Creek recently expanded facilities through large-scale capital campaign drives. Three years ago, the outdoor Peg Egan Performing Arts Center opened in Egg Harbor, offering for free some of the same acts the DCA once offered exclusively.

The struggle to build the county’s first year round performing arts centers is largely forgotten, and today it must compete as just another of many venues offering an entertainment product.

Kaaren Northrop, President of the DCA Board of Directors, said the organization is adjusting to the more competitive market. “It totally changes what we need to do. We have to offer what nobody else can.”

This year Terry Meyer-Matier, who served as the auditorium’s executive director through much of the 1990s, is back working on main stage programming for 2010. She has been the programming director for Big Top Chatauqua in Washburn, Wisconsin since leaving the auditorium in 2000 and was recently named that organization’s executive director.

Northrop is excited to have Meyer-Matier back in the fold, and looks forward to moving ahead after a restructuring that included the hiring of a new executive director in April. She said more local acts will grace the stage and more school children will fill the seats in a re-dedication to its strong community roots.

A return to the glory days won’t be easy, but when one looks back at the early struggle for the Door Community Auditorium, to expect easy would be naïve.

“The struggle is why I care so much about the place, because we did have to work so hard,” said Haberland. After a decade away from the auditorium’s board of directors, she accepted their invitation to help them find a new executive director. “I want to see someone with a big vision come in there. I want to see kids in the seats, and children running through the halls of the Link Gallery. You have to get them all in there, because you never know when you might have someone in there who might change a life.”