The Legacy of an Industry: Quarrying for Stone in Door County

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

“Door County’s first export consisted of stone.”

~ Hjalmar Holand from History of Door County, Wisconsin: The County Beautiful, Volume I

Today, Door County thrives on the tourism industry; however, this was not always the case. During the mid-19th and well into the 20th century, the textured landscape and surrounding water served as more than a backdrop for quaint villages. The abundance of exposed rock and the ease with which it could be transported via water provided the basis for a successful stone quarry industry in Door County during the initial phase of harbor construction around the Great Lakes.

The Door Peninsula is part of a unique geological formation – the Niagara Escarpment. The foundation for the Niagara Escarpment, a prominent line of bluffs that stretches from its namesake, Niagara Falls, in a horseshoe shape through Ontario, along the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, down the Door Peninsula, and toward Horicon Marsh, was formed more than 400 million years ago when sediment was deposited on the floor of an ocean that covered much of the continent during the Silurian Age. After much shifting of the continents and the advance and retreat of glaciers over this region, softer layers of the bedrock eroded and an exposed rock ridge of dolomite, a limestone rich in magnesium which may also be referred to as dolostone, remained.

The characteristics of the dolomite found in Door County made it ideal for certain practices and less than ideal for others. Some of the stone removed from the landscape was used in the production of lime or flux while relatively minor amounts of stone were used for building construction. For the most part, the dimension stone quarried from Door County was either rip rap or rubble stone – pieces of stone weighing between two to five tons or 50 to 100 pounds, respectively. These slabs were ideal for the construction of harbors because they posed less risk of fire damage than wood and were very resistant to erosion.

According to Stanley Greene’s article on the city of Sturgeon Bay’s “Golden Age of Stone,” which appeared in the June 10, 1976 issue of the Door County Advocate, one of the first individuals to draw attention to the prime location for a quarry along the shores of the Door Peninsula was Samuel Straumbaugh, the Indian Agent at Fort Howard in the 1830s. His reports extolling the virtues of the quality and quantity of the stone as well as the “commodious and beautiful” harbor near Sturgeon Bay encouraged the government to open a quarry.

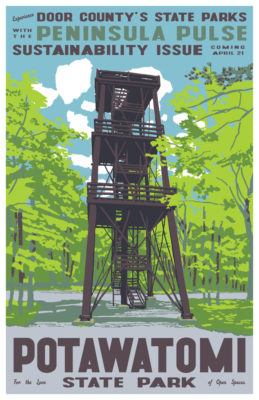

Upon Straumbaugh’s recommendation, a Government Reservation secured 100 acres of land overlooking Sawyer Harbor, which is currently the site of Potawatomi State Park. After obtaining a permit from the federal government, as mentioned in M. Marvin Lotz’s book Discovering Door County’s Past, a company of Green Bay men had opened a quarry at the location by 1834 under the condition “that the stone be sold only for the purpose of building breakwaters and harbors.” This quarry came to be known as Government Bluff.

Other locations along the peninsula soon followed suit, hoping to capitalize on the demand for stone as major cities grew around the shores of the Great Lakes. Small quarry operations opened at Baileys Harbor, Door Bluff, Eagle Bluff, Garrett Bay, Marshall’s Point, Mud Bay, and on Washington Island. Some of these quarries achieved success. According to Lotz, the quarry at Garrett Bay, for instance, “stayed in operation for over a decade supporting a general store, boarding house, blacksmith shop and pier for the loading of stone into barges.”

Others, however, had a more difficult time, like the quarry at Door Bluff as recalled by Hjalmar Holand in the History of Door County: “The character of rock there led to the belief that it contained marble of fine quality…and preparations were made for extensive operations…village lots were laid out on the summit of the bluff, and a large pier was constructed. The marble proved to be a delusion, however, and the works were abandoned after a few cargoes had been shipped.”

The opening of the canal in Sturgeon Bay in 1881 changed the dynamic of quarrying in Door County; it made large-scale commercial quarries possible. Greene pointed out that “by the beginning of the Twentieth Century eight major quarry sites had been opened on Sturgeon Bay, and two of them had been closed.”

Then in 1903, there was a merger of two quarries in Sturgeon Bay, bringing the number of active companies to four: the Green Quarry, the Laurie Quarry, the Leathem and Smith Quarry, and the Sturgeon Bay Stone Company. As smaller quarries within the Sturgeon Bay market closed because they could not compete, the majority of the outlying quarries on the peninsula also closed.

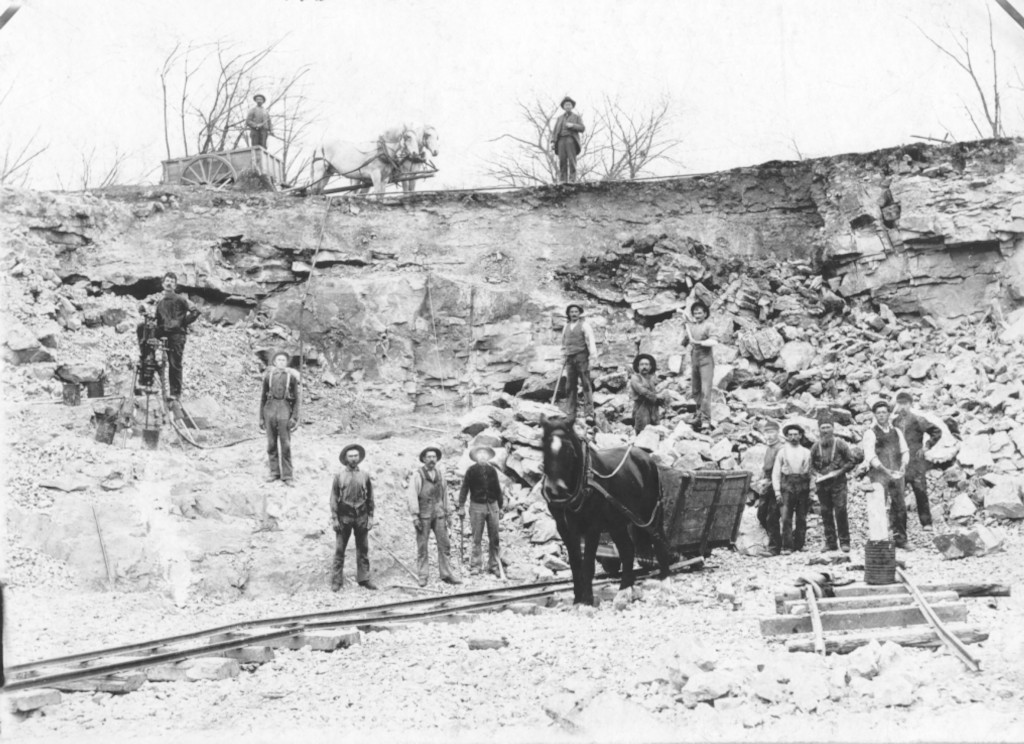

During this time of commercialization, the process of quarrying evolved greatly. In Victoria Dirst’s “Second Report on the Leathem and Smith Quarry in Door County,” which was published by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, she explains how the work initially relied on manpower to pry loose slabs of rock with crowbars in excess of 300 pounds and then horse-drawn carts were utilized to get the rock to the waterside. Black powder came into use in the 1880s and eventually dynamite and steam-powered machinery was widely used. According to Holand, “A ton or more of dynamite [was] used in one explosion, throwing down 20,000 tons of rock in a single blast.”

With the ever-increasing efficiency of removing rocks from the bluffs, there came a time in the industry when transportation of the stone became as important as quarrying itself. As companies merged, they combined their shipping fleets to try to meet the demand for stone around the Great Lakes. Local shipyards also converted a large number of old wooden sailing ships, removing their masts and leaving the bodies of the ships an open vessel into which stone could be loaded and then towed by other ships to its destination. Greene provides an account of a quarry in Sturgeon Bay contracted to deliver 2,700 cords of stone to Ludington. In order “to make the delivery in the allotted amount of time the company tug had to make three round trips each week towing two stone carriers.” Apparently it was not uncommon for the bridge over the canal to be opened 40 times a day during the stone shipping season, which began at ice out in early spring and continued through Thanksgiving.

As World War I broke out, civic building projects came to a halt and the quarries in Door County had a difficult time staying in business. Lotz states, “Basically, when the period of harbor building on Lake Michigan ended, so did the life span of many of the quarries.” However, it should be noted that by the time Holand’s book was first printed in 1917, “millions of tons of Door County stone [had] been used in harbor improvement. Almost every harbor on Lake Michigan was built in part with Door County stone.”

One quarry that stayed in business beyond this difficult time was the Leathem and Smith Quarry because they provided crushed stone in addition to dimension stone. The quarry started providing crushed stone in 1903, and when Thomas Smith’s son, Leathem D. Smith, inherited the quarry in 1914 he hired the Nebel Electric Company to completely electrify the crushing plant, which then became known as the L.D. Smith Stone Co. The company thrived, employing more than 100 men.

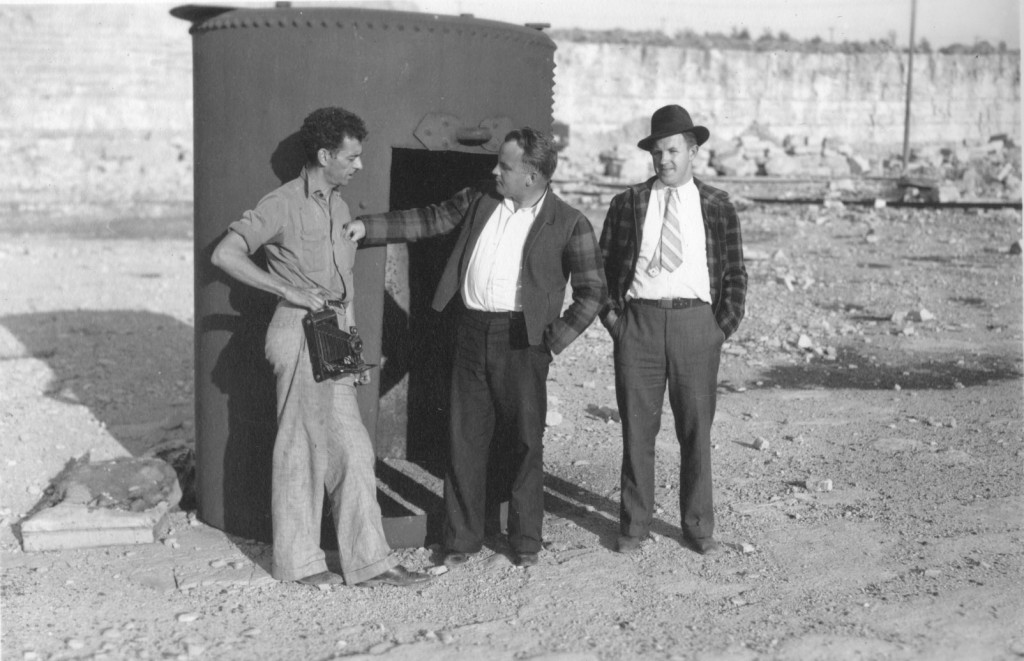

“Then in October 1927,” says Lotz, “the largest business deal ever transacted in the history of the county was finalized when a Cleveland, Ohio company bought the controlling stock of the L.D. Smith Stone Co. for $675,000.” When Dolomite, Inc. purchased the quarry they renamed it the Sturgeon Bay Company and had high hopes for the future of the quarry; however, by the 1930s this quarry was affected by the Depression. Holding on longer than most others, in 1944 the plant was dismantled and the equipment was shipped to Drummond Island, Michigan. Within the last decade, the site of this quarry has been cleaned up and transformed into Olde Stone Quarry County Park.

Although there are a small number of active quarries in Door County today, their impact on the economy is not as apparent as that of earlier quarries. Traveling through the county, one might not even notice the impact this industry made to Door County’s past as many of the scars on the landscape have healed naturally. The legacy of the stone industry, however, remains in many of the harbors dotting the shores of the Great Lakes.

Resources:

“Second Report on the Leathen and Smith Quarry in Door County” by Victoria Dirst. Published by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Bureau Property Management, December 1, 1994.

“Quarries Provided City ‘Golden Age of Stone,’” by Stanley Greene. Door County Advocate, June 10, 1976.

History of Door County, Wisconsin: The County Beautiful, Volume I by Hjalmar R. Holand. Wm. Caxton Ltd., Ellison Bay, WI, 1993.

Discovering Door County’s Past: A Comprehensive History of the Door Peninsula in Two Volumes, Volume I by Marvin M. Lotz. Holly House Press, Fish Creek, WI 1994.