Chateau Hutter: Door County’s Grand Resort that Never Was

- Share

- Tweet

- Pin

- Share

Maybe it’s the name, tasting of a past barely tangible. Maybe it’s the location, nestled into the quiet stretch of shoreline between Sturgeon Bay and Egg Harbor along Bay Shore Drive, hiding on the scenic shortcut so many locals turn to when summer weekend traffic backs up Highway 42. Like the crumbling barns of the county’s dying farms, the idleness of this old resort evokes a sadness for an era lost or a dream unrealized.

The name of the property is chiseled into the weathered wood of the sign the way a boyfriend might carve his girlfriend’s name into Eagle Tower. From out here at the road’s edge, it’s just that, a property with a name, but no cars, no people, just a collection of buildings in the distance.

This is Chateau Hutter, the grand resort that never was.

The Chateau Hutter sign remains on Bay Shore Drive near Sturgeon Bay. Photo by Matthew Smith.

Not a Humble Man

John A. Hutter loved to travel and enjoyed fine meals. An accountant by trade from Chicago’s north side, he fancied himself a filmmaker and produced travelogues of his journeys to show to his friends and students at DePaul University, where he taught.

When Hutter fell in love with Door County, he dreamed of bringing the best of his experiences from around the world to the peninsula, taking the Midwest vacation experience to another level and showing the townfolk of Egg Harbor how a great resort should be run.

Like many before him and hundreds to come after him to this peninsula, his aspirations were greater than his abilities.

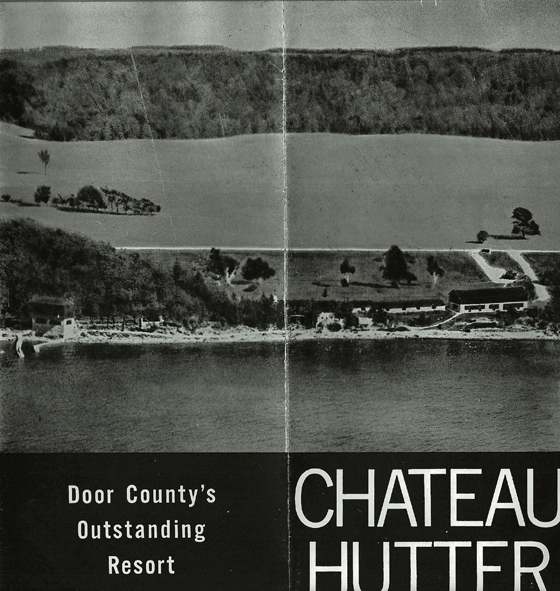

In the late 1940s he acquired 320 acres of land about nine miles north of Sturgeon Bay on Bay Shore Drive. About 1950 he opened Chateau Hutter, a complex of four buildings constructed in 1944, built with stone from the nearby beaches and woods and pine harvested from the bluffs across the field.

Hutter aimed to create a resort that recalled the “exotic atmosphere of a chalet in Switzerland” and claimed to have traveled with his wife Clara to every continent to study the world’s foremost hotels and restaurants so they “might establish a truly outstanding summer mecca of gay relaxation” in Door County.

“The most beautiful flowers in Door County will remind you of Anne Hathaway’s garden at Stratford-on Avon,” Hutter wrote in the lengthy copy included in a 1950s brochure. It was one of many examples of overpromising from Hutter, a habit that would get him in trouble often in the years to come.

By all accounts the resort was beautiful in its day, and pictures from Hutter’s brochure display a summer retreat that aimed for a feel like that of the Alpine Resort a few miles further up Bay Shore Drive in Egg Harbor. Hutter, in fact, seemed to model the property on the Alpine, with lodging, a restaurant, and plans for a 27-hole golf course. Bill Bertschinger, who has been working the Alpine property for all of his 80-plus years, recalled Hutter hanging around the Alpine to take notes on the operation.

About 1950 he created a promotional video, Four Seasons in Door County, for Chateau Hutter that has the feel of a director channeling Rod Sterling’s Twilight Zone-style for a travelogue. It begins with Hutter speaking directly to the viewer from a large chair in a library.

“It has been my business to create motion pictures all over the world,” Hutter says, but what he presents is a self-narrated home movie featuring guests struggling to pull a rowboat ashore on the rocky beach of Chateau Hutter and bathers slipping and sliding on rocks as they try to enter the water. It may be the only promotional video featuring a couple digging their car out of the deep snow of a Door County ditch.

However odd the video, we do owe Hutter thanks. His ode to the peninsula provides a fascinating time capsule of a Door County long lost. There’s extensive footage of the old Potawatomi State Park ski hill and toboggan run; a journey up to Egg Harbor on the then-narrow, canopied Bay Shore Drive; a ferry ride to Washington Island across the “Door of Death”; and old images from the Door County Fair.

Hutter’s advertising labeled Chateau Hutter “Door County’s Outstanding Resort,” and claimed that “only on the French Riviera will you find a comparable environment,” but reality painted a far different picture.

Over-promise, Under-deliver

While the Alpine Resort thrived, Chateau Hutter struggled.

Hutter claimed a world-class golf course. In reality, it was designed and shoddily built by Hutter himself.

“He always thought he could make another Alpine,” recalled reporter and Egg Harbor historian John Enigl, “but I think he only finished one hole of the golf course. I don’t know if it ever really was a fully functioning resort that I can recall.”

After a fire in the mid-1960s, Hutter was said to have swept up the ashes and re-opened, a final straw for many competing business owners who had grown irritated of Hutter’s grand claims. In 1965 the Door County Chamber of Commerce refused to accept his dues and expelled him from membership. Bertschinger was chamber president at the time.

“He was promising things he never delivered and prostituting the Door County brand,” Bertschinger said.

Enigl backed up Bertschinger’s recollection. “He would advertise meals and people would go there, see the place and think it was kind of weird, and walk right out.”

Hutter believed he was was the victim of a mean-spirited campaign by Door County’s good old boy network and claimed that he was forced out of the Chamber and slandered by Bertschinger and other business owners because he presented stiff competition to their businesses. Bertschinger remembered it differently.

The walkway along a rocky shore that Hutter disingenuously promoted as a wonderful place to swim. The image is from a Chateau Hutter brochure.

“We loved having him down there,” Bertschinger said. “People would come up, check in at Chateau Hutter on Friday, then check out Saturday and drive up here to us.”

Hutter filed suit against the Door County Chamber of Commerce, claiming that his expulsion put him out of business. James Smith was a young attorney finishing law school at the time. Chamber attorney Sven Kierkegaard invited him to sit in on the proceedings, which provided valuable lessons to the young lawyer.

“It certainly showed me you don’t go to court without a lawyer who knows what he’s doing,” Smith said.

Hutter was a licensed attorney who had never tried a case, but he chose to represent himself in the case, which he lost. When he appealed to the United States Court of Claims, the decision included harsh words for his legal abilities.

“Though he was cited as an experienced attorney, the record doesn’t support that,” the review reads. Hutter’s complaint was “obviously drafted by a pro se plaintiff with little or no experience in pleading or practice.”

At one point during questioning, Hutter grew tired of the defense counsel’s objections (there were 1,280 in all), leading to the following exchange between Hutter (Plaintiff) and the presiding judge:

Plaintiff: It seems to me, your Honor, that this is about the time now when our opponent here, opposing counsel, should state the reason for his objection.

Judge: I will state the reason because I am the one who must assume the responsibility for the rulings. The objections to all of these questions have been sustained because the questions are not proper under the law of evidence.

Plaintiff: Why?

The Court: I don’t – I am not a lecturer here. I used to teach but I gave that up, Mr. Hutter. I am not employed here as a lecturer on the law of evidence. I tell you as a matter of law of evidence the questions are improper and it is not incumbent on a trial judge to tell a lawyer how to ask his questions, if, indeed, they can be asked properly. That will be the only reply I care to make to your question.

The chairs of the grand veranda sit empty, as they have for nearly the entire existence of the resort. Photo by Len Villano

Hutter would spend much of his later years mired in legal battles. His suit against the Chamber rambled on for five years and three appeals, resulting in little but extensive legal expenses for the Chamber. Back home in Chicago, where he owned an apartment building, he battled the city over whether his building had proper fire exits and sued the City of Chicago for half a billion dollars. In 1971 Hutter turned his ire to the Town of Egg Harbor, upset over his property tax assessments.

He argued that his property should be taxed as agricultural land, not as a resort. Enigl, who reported on the proceedings, said Hutter tried to claim the buildings were simply storage for his tractors. Meanwhile, he was still advertising the property as a resort in the Chicago area. He eventually appealed to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, and in his petition for re-hearing he said the shore frontage was useless. “It is all solid precipitous moss covered rock. Bathing is not possible,” he wrote. Furthermore, “no one would want to eat and what good would it do them if they did, for there would be no place to use a toilet.”

This was in direct odds with what Hutter advertised for years, when he claimed in brochures that “the bathing is most enjoyable.”

“Hutter thought the people up here were fools,” Enigl remembered. “He thought he could come here and tell them how things should be done. Watching his arguments with the town you could see he thought we were a bunch of hicks.”

His petition rambled for 20 pages, claiming that he was railroaded because he was an outsider, forced to pay discriminatory, confiscatory, unconstitutional taxes. He compared his plight to that of the American Indians and Civil Rights activists.

“You can use your local Chamber to slander, libel, and exclude the intruder,” Hutter wrote. “This is an excellent example of how these types from other states may be dealt with to keep all goodies for the well entrenched local establishment.”

He likened Egg Harbor Town Chairman Milton Haen to powerful Chicago Mayor Richard Daley.

Bill Anschutz, who served on the board with Haen, said Hutter “would get Milton so mad I thought he was going to have a heart attack.”

A Half Century of Rumors

For nearly 50 years Chateau Hutter has been little more than a mystery to most. Much of the acreage was sold off, some to condo developers in the late 1970s and 186 acres to the Door County Land Trust in 1999, for $1.2 million. That parcel is now part of the Bay Shore Blufflands Preserve, but does not include the remaining building of Chateau Hutter or another 80 acres on the east side of Bay Shore Drive.

New plans for the property surface every few years, some as rumors – a golf course, condos, a nature preserve – others as real proposals – a music camp for handicapped children – but nothing has come to fruition. Since Hutter’s death Al Beaver has overseen the property as president of the Chateau Hutter Conservation Corporation, a non-stock, nonprofit corporation. Beaver represented Hutter in a fraud dispute he won in the late 1980s and has been managing the property ever since.

Two of the larger buildings have been restored, Beaver says, with a commercial kitchen, rustic dining room and lounge and a huge granite fireplace. He still hopes to create something from the bones of the buildings, but even today the property is mired in litigation.

Inside the buildings, which have been victimized by the occasional vandal and the wear of decades without use, one can still see the furnishings of a resort that once aimed for grandeur, but never achieved it.